At the World Economic Forum in Davos last week, President Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, unveiled his Plan for “New Gaza” envisaged by the new Board of Peace created by his father-in-law. Kushner’s presentation looked more like a giant real-estate deal than an acknowledgement of the enormity of the military onslaught that has killed over 70,000 Palestinians in just over two years, or of the rights of the survivors to agency over their own future. The people of Gaza were to be the recipients of a bigger project designed and controlled by others. The gleaming tower blocks portrayed in Kushner’s presentation couid not obscure a fundamental denial of Palestinians’ right to sovereignty in their own land.

But the Board of Peace is not about the rights of the people of Palestine or of anywhere else. Gaza is but one project in something much, much bigger. The Board of Peace is about Trump giving himself imperial power to replace the authority of the United Nations globally with a fiefdom of his own, aided by hand-picked friends and with business opportunities galore for his family. I do not use the word fiefdom lightly. Read its founding Charter and you will see that the Board of Peace is designed to be Trump’s own property for a long as he wants to personally control it. Indeed, it even gives him the authority to choose his own successor.

For the best analysis I have seen so far of what the Board of Peace is, who is on it and what it means for our world, I recommend this from Hugh Lovatt, Senior Research Fellow of the European Council on Foreign Relations. I have reproduced it here with his kind permission:

Welcome to the jungle: Trump’s Board of Peace goes global

The US president’s Board of Peace has less to do with peace, in Gaza or elsewhere, and more to do with enforcing a new, transactional global order. Welcome to the America-First Trumpian world

President Donald Trump’s Board of Peace (BoP) is not much of a peace mechanism. Look no further than its logo—a US-first western hemisphere flanked by rip-off UN olive branches burnished in Trumpian gold—to see the BoP for what it really is: a top-down project to assert Trump’s control over global affairs.

At its Davos inauguration, the US president delivered a rambling speech to the 19 countries present, hailing them “the most powerful people in the world.” Belarus’s autocratic leader and an early BoP signatory, Aleksandr Lukashenko, was unable to attend due to European sanctions over human rights abuses. Binyamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, was also absent, facing an International Criminal Court arrest warrant over alleged war crimes in Gaza.

After Trump’s “top leaders” were presented, Jared Kushner unveiled a $30bn “Trump development plan” for “New Gaza.” Complete with a skyscraper-crammed coastline, the vision would see the wholesale bulldozing of the Strip to create a newly engineered society and economy under BoP supervision. Judging by the Arabic spelling mistakes in the PowerPoint presentation, no Palestinians were consulted on their “prosperous future”.

What began with a mandate to implement Washington’s Gaza ceasefire plan, as enshrined in UN Security Council resolution 2803, has morphed into a personal vehicle for a Trumpist world order. The BoP’s charter omits any reference to Gaza and echoes Trump’s criticism of the UN, calling for “courage to depart from…institutions that have often failed” by establishing a “a more nimble and effective international peace-building body”.

European leaders broadly backed resolution 2803, but have avoided the BoP (bar Hungary and Bulgaria), expressing concerns over its mandate, legality and challenge to the UN. They are right to stay away: the board’s purpose, governance and financial entanglements risk legitimising a system in which loyalty and money outweigh international law. Joining such a body would dilute Europe’s voice and erode what remains of the multilateral rules-based system.

How the Board of Peace works

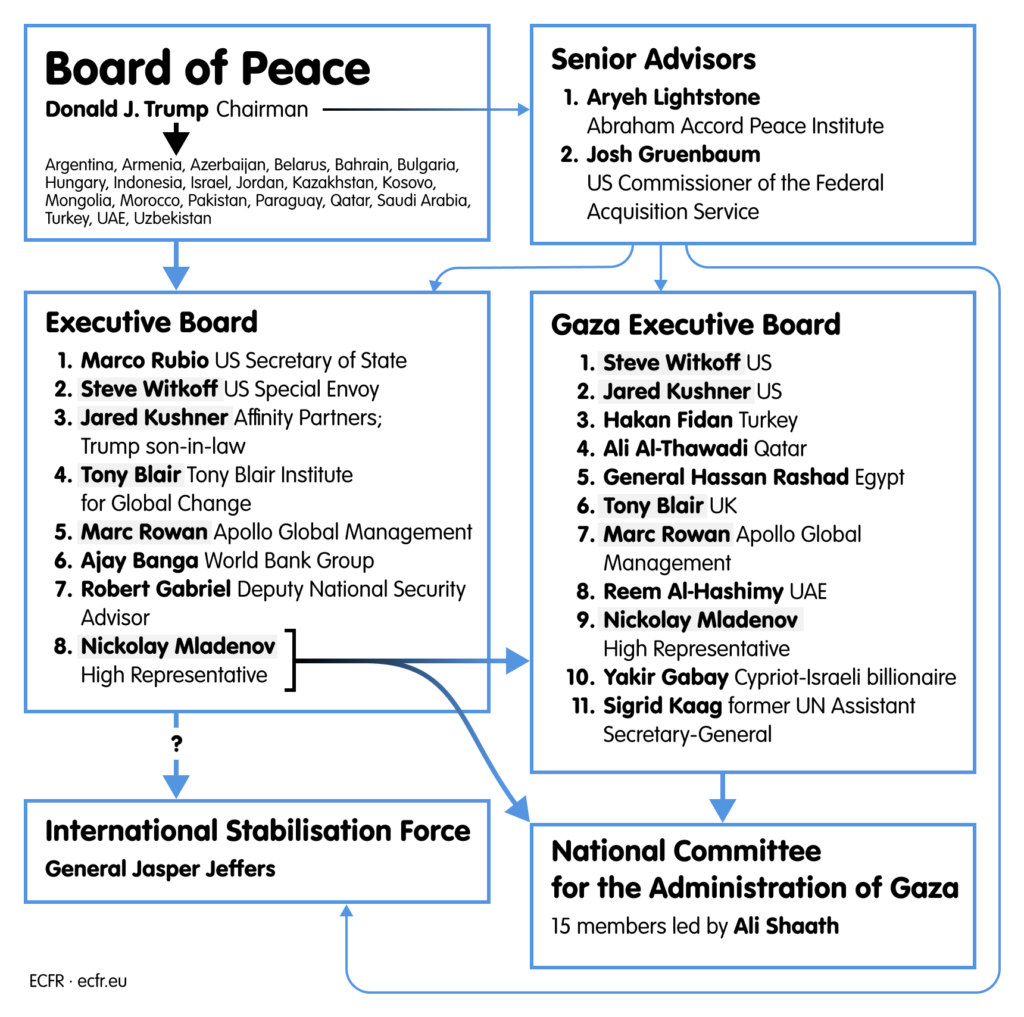

The BoP can be thought of as a Trump-owned US company, with the US president as permanent chairman and majority shareholder. According to the board’s charter, all decisions and power emanate from Trump as he selects and presides over a subordinate governing board of member states.

Board members will serve three-year terms, renewable at the chairman’s discretion. Out of the 50-60 countries invited, 21 have so far joined. Many no doubt value the opportunity of a closer, more transactional US relationship. Others share Trump’s hostility to the UN-sponsored liberal order. Together, they will vote on the BoP’s budget, international agreements and “peace-building initiatives”, with only a simple majority—and the approval of the chairman—required.

While the charter describes funding as voluntary, Trump’s track record suggests he will press members to “pay up”, with big payers likely to have the most influence. (Those paying $1bn will be given permanent membership.)

Trump also has the power to dismiss board members “subject to a veto by a 2/3 majority of Member States”. In practice, convincing two-thirds of BoP members to directly oppose Trump on such matters will be a high bar to reach for any blocking majority. Those members that step out of line risk the diplomatic humiliation of being fired by Trump as if they were contestants on The Apprentice. He has already revoked Canada’s invitation after prime minister Mark Carney’s Davos speech called for middle powers to develop greater strategic autonomy.

Below the board is an executive board and CEO appointed by Trump. This is where the power lies, tasked with day-to-day running of the BoP and the managing of funds. It also has the mandate to set the agenda for each board meeting, further reducing member-state autonomy.

Among its members are senior US officials and businessmen: Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law and founder of Affinity Partners, an American investment firm with close ties to Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds; Marc Rowan, CEO of asset management firm Apollo Global Management which invests in private equity and real estate; and Ajay Banga, another business executive and president of the World Bank Group.

The mixture of private investment funds with American power and geopolitics, combined with likely opaque decision-making and financial expenditure is a recipe for kleptocratic oligarchy. Already, the Guardian is reporting that Albania joined the BoP just as Kushner gained approval from the Albanian government to build a $1.4bn luxury resort on Sazan island. Meanwhile, Bulgaria’s outgoing prime minister, Rosen Zhelyazkov, reportedly joined the BoP at the urging of a Bulgarian oligarch sanctioned by the US for corruption.

What this means for Gaza

The BoP has several subsidiary entities focused on Gaza, which Trump has “exclusive authority to create, modify, or dissolve.” First is the Gaza Executive Board to oversee the implementation of Trump’s 20-point plan, including a Palestinian National Committee for the Administration of Gaza (NCAG). Composed of 15 members led by Ali Shaath and charged with Gaza’s day-to-day management, the NCAG sits at the bottom of the hierarchy with little influence or agency. So far, Israel has not even let members into the war-torn Strip.

As per the 20-point plan, the BoP will also establish a Gaza International Stabilisation Force (ISF) led by American General Jasper Jeffers, though it is not clear who in the BoP he will report to. Questions similarly remain over the scope of the ISF’s mandate to enforce the disarmament of Hamas and other armed groups in Gaza.

In addition, Trump has appointed two White House advisors, Aryeh Lightstone and Josh Gruenbaum, as senior BoP advisors. They will be enforcers of Trump’s writ. Lightstone’s background should be cause for concern: He was an advisor to former US ambassador David Friedman and is a “staunch defender” of Israel’s settlement project. He was also reportedly involved in establishing the disastrous Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (which caused the deaths of numerous Gazan aid seekers) and is now working through the Gaza Civil-Military Coordination Center (CMCC) to develop US plans for post-conflict Gaza.1

Having long asserted that the US will “take over” and “own” Gaza, Trump now wields near-total control of the Strip through the BoP. The involvement of private investment funds, many with real-estate interests, reinforces his vision of a US-backed, corporate-built “Gazan Riviera” as showcased in Davos on Thursday.

A week earlier, the CMCC had already moved in this direction, reportedly presenting plans for a “Gaza First Planned Community” designed to house up to 25,000 Palestinians in a residential neighbourhood built on the ruins of Rafah. The scheme appears to revive Israeli plans for “humanitarian bubbles” of “Hamas-free” areas secured by foreign contractors, with residents subject to relentless external vetting and biometric checks. Such an approach would deepen Gaza’s territorial and societal fragmentation and do little to counter Hamas, which remains deeply imbedded in Palestinian politics and society.

The main checks on Trump’s “Gazan Riveria” vision will be Hamas’s continued control on the ground but also the extent to which Arab members of the BoP can push back internally and condition their funding on a more holistic reconstruction, predicated on Israel’s full withdrawal from Gaza and the return of the PA.

What Europeans can do

Outside the Trump-controlled BoP, European states have significant influence. They should engage directly with the Gaza Executive Committee which is more in line with UNSCR 2803 and where there is strong European representation through Nikolay Mladenov, Tony Blair and Sigrid Kaag. Arab partners such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia who are represented on both the board and Gaza Executive Committee are also indispensable partners in shaping BoP actions from the inside.

Being relevant on Gaza does not mean toeing the US-line. It means making commitments to empower the Palestinian National Committee as it comes under tremendous pressure to follow the US and potentially sign murky real estate development deals. Such deals might generate profits for the BoP’s investment fund, but will do little to support ordinary Gazans who want to rebuild their homes and communities in safety and unlock economic re-development (which requires an end to Israel’s decades-long siege of the Strip).

European states should also look for ways to support the ISF once concerns over its mandate and command and control structure are addressed. This could include funding, technical support, and even limited troop contributions (as they have done in other peacekeeping missions). By being proactive, Europeans would strengthen their hand with Trump, who remains the best hope of pressing Netanyahu into a full withdrawal from Gaza and broader Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations.

Multilateralism in a Trumpist world

The BoP is unlikely to translate into a full US exit from the UN given its Security Council veto power. But it could spell further funding cuts and withdrawal from UN agencies, and the channelling of US diplomatic engagement into the BoP to assert America’s agenda for controlling the global order. The European counter-proposal to the Ukraine-Russia ceasefire envisaged the BoP as part of the deal, and the board could be expanded to Venezuela or other areas of interest to the US president such as Greenland or Iran.

For all his effort, Trump is unlikely to replace the UN given its deep anchoring in international governance and the BoP’s limited membership which still lacks key countries such as Russia and China, any African state, and most of Europe. Even if the BoP does gain traction in the coming years, it is unlikely to outlive Trump’s presidency. The far bigger danger is that in attempting to impose the Trumpian order on Gaza and the world, European countries will have little of the old liberal international order to fall back on once he is gone.

In the meantime, Europeans should influence the BoP’s positions. They are unlikely to be able to do this from inside given Trump’s tight control. Currying the presidents favour by joining the BoP is doubtful to shift US policy on Greenland, Ukraine, European security or his penchant for tariffs. More likely, it would re-enforce Trump’s view that Europeans are weak and will fall in line with him one way or another.

European countries are stronger when they hold the line together in defence of European interests. On Greenland, for example, their collective pushback forced Trump to climb down—at least for the time being. With this in mind, Europeans should engage with the BoP on specific issues from the outside and work with partners on the inside. The goal should be to shape BoP engagement in line with Europe’s vision for peace in Ukraine, Israel-Palestine and the broader Middle East where renewed US strikes on Iran risk renewed regional convulsion.

But Europeans should also be aware of the dangers of short-term transnationalism. By buying into the BoP, they would risk legitimising a Trumpian order centred on the president and his reversion to 19th century geopolitics where might is right and territorial conquest by great powers is legitimate. With the rules-based order already in trouble before Trump’s return to the White House, Europe will have to look to itself to secure its interests.

- ECFR discussions with European, Israeli and Arab officials and experts working on Gaza over the past year. ↩︎